Giraffes are a truly African mammal. While elephants’, leopards’ and even lions’ ranges extend into Asia, these unique mammals are special to sub-Saharan Africa.

These mammals are best known for their long legs and long necks, evolutionary modifications that give them access to forage beyond the reach of almost all other herbivores (only the largest elephants can reach higher). They’re almost exclusively browsers, feeding on leaves and flowers which they gather with a long – almost prehensile – tongue. However, they are also partial to Sausage fruits when they are very small!

The population of giraffes found in the Luangwa became separated from other giraffes in Africa as the Great Rift Valley formed; the steep escarpments bounding the area prevented the giraffes spreading and mixing. Selection pressure led to divergent evolution such that, in the early 20th century, they were declared a distinct sub-species – Thornicroft’s Giraffe. They are smaller than other sub-species and their pattern markings do not extend below their knees.

They live in loose herds, dominated by a large bull, of females with calves and a varying number of sub-adult males. Calves are suckled by their mother, but are often left in creches guarded – not very closely – by an adult female. Perhaps because of this creche tendency, but more likely because they do not seem to be very attentive mothers, calf mortality is very high, perhaps reaching 50% in the first year.

Large bulls are distinctive due to their intensely dark pelage and bony skulls. From around the age of 8, bull giraffes’ pelage begins to darken starting on the shoulder and spreading across the body. The final area to change is the neck by around age 10-11 years old.

During this time, bone is deposited across the front of the skull, adding bulk to the head – in time, this gives their faces a ‘lumpy’ appearance.

Young giraffe bulls spar gently by standing shoulder-to-shoulder and wrestling with their necks and heads. In a severe fight, which would only occur between two evenly matched bulls, this develops into ‘necking’ where both bulls attempt to land blows on the other’s flanks, using their heads and necks as golf clubs. It is a terrible event to observe. Fortunately, prior to any battle, there is posturing and controlled jostling which often reveals the stronger male before any damage is done.

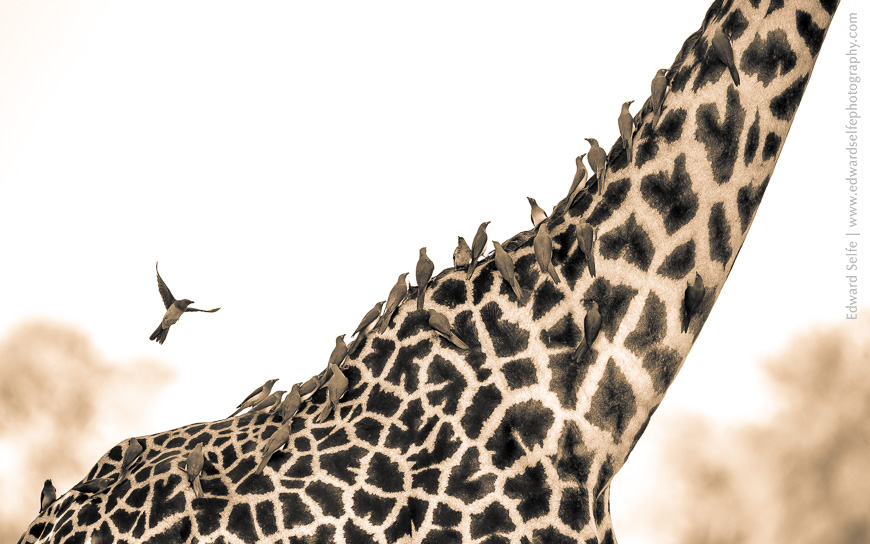

Possibly due to this brutality, males live considerably shorter lives than females, perhaps reaching only 20 years old while their ‘wives’ live on to nearly 30 years! Giraffes are always attended by a host of Oxpeckers of both species. These starling-like birds make a living from the parasites which feed off large mammals.

Perhaps most endearing of all is giraffes’ curiosity. I have stopped for a tea-break on a walking safari with guests and been approached by a large herd of giraffes, keen to investigate what we were doing. I’ve also seen giraffes approach a lion feeding on an eland carcass, standing nearby for half an hour observing the predator from less than 30 metres away!

I also watched – over a few days – as a herd appeared to ‘mourn’ the loss of one of their number. A female died over complications with pregnancy and was quickly exploited by scavengers. But each day, the rest of the herd would stop and watch as the vultures squabbled and the hyaenas chewed on the remains. It’s anthropomorphism to suggest that it was mourning, but their curiosity certainly extended beyond simply observing something that caught their eye.

There may be only 500 or so Thornicroft’s giraffe on the continent, but you’re certain to see them on a visit to the South Luangwa. They’re ubiquitous throughout the dry season, only retreating to drier ground away from the river in the rains when their long legs and relatively small feet don’t deal so well with the mud!